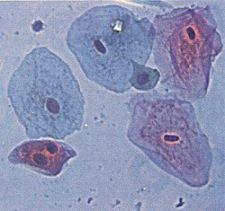

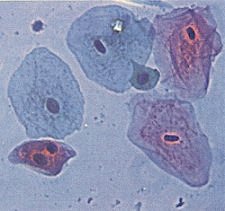

By the mid 1700’s early microscope users had realized that living cells contain a light gray sap with a darker, denser globule floating about in the sap. This structure is easily noted in the images of the stained human cheek cells to the right.

In 1831, Robert Brown used the word

nucleus to describe the dark, central globule. The word nucleus is Latin for little nut. The nucleus of most cells averages about 5 μm (.005 mm) in diameter. It is surrounded by the

nuclear envelope, a double membrane made of proteins and lipids that separates it from the cytoplasm.

Early on in the microscopic study of cells, it was found that adding stains or dyes to thinly sliced tissue caused some structures inside cells to stand out. The material in the nucleus absorbed stains so readily that it was named

chromatin (from the Greek chroma = color.) The cells in the image at the upper right are stained human cheek cells. Staining and observing cheek cells is a typical lab exercise done as part of the high school biology curriculum. It is even possible to

prepare and look at cheek cells with a good quality toy microscope in your own kitchen.

To the early observers, the chromatin appeared to be tiny granules or delicately intertwined threads scattered about inside the nucleus. Today we know that

chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein that forms exceedingly long, thin, entangled threads called

chromosomes (from the Greek chroma = color + soma = body). Only when the

nucleus prepares to divide do the chromosomes condense and become thick enough to be seen through a light microscope as separate structures.

Each species has a characteristic number of chromosomes.

The human body is made of approximity 37 trillion cells. Each of those cells except for red blood cells and sperm and egg cells has a nucleus. Each human nucleus has 46 chromosomes.